-

A Look Back

Seeing as how 2023 is already speeding by (Tomorrow is the 3rd of January! Already!!!) I thought it was time to take a nostalgic look back on the 2020s so far:

What the fuck? Seriously, what the genuine fuck just happened? Did we really go through two years of pandemic-induced hell, only to be rewarded with whatever fresh hell 2023 is preparing to throw at us? (I am, of course, referencing the pandemic-induced hell unleashed on my small island, as that is the only one I experienced first-hand; your pandemic may vary.)

During the past 36 months, we have spent 27 of them enduring some form of Lockdown, and compared to many others, we got off lightly, but I doubt many other countries had the pleasure of seeing their leaders partying, carousing, and necking it their offices with co-workers while the rest of us were being forced—under threat of arrest—to remain inside and isolated.

In case you were tempted to forget. (And that leads into what 2023 might have in store for us, as the same gang—different leader, same gang—remains in charge. But we’re not going there. Yet.)

Boris fiddled while Britain burned, Truss went down in flames and took the economy with her, and Rish! is stirring the ashes and hoping for a miracle. What surprised me most about the easing of the pandemic was the speed at which it was being forgotten. A year ago, we were in lockdown. Two years ago, we were in a hard lockdown, and three years ago, we were getting ready to dive, head-first, into one. You’d think a scar that deep would leave a lasting impression, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Evidence of the erstwhile pandemic are already fading, like the rusting relics of The War. But unlike the War, people don’t seem to want to remember; they just want to leave it behind.

Relics of the past. In retrospect, I should have seen this coming.

In 2018, I was writing a book set in 1918. I knew from history lessons that a deadly pandemic had made the rounds at that time, but the research I did into who was doing what, and how life was lived during that era turned up scarce few mentions of the plague that cost the lives of between 20 and 55 million people.

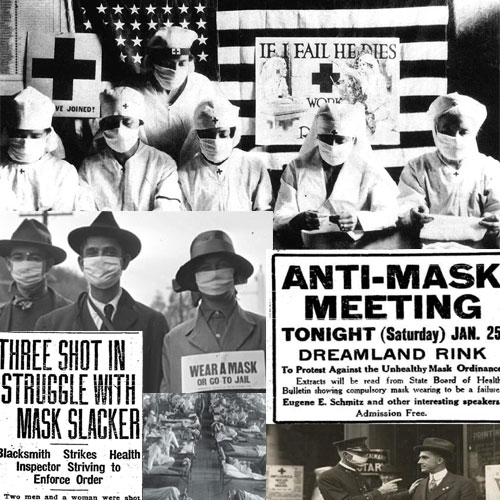

Fast forward to now, when I am revising said manuscript, and you can’t Google 1918 without turning up a raft of articles detailing those dark times, accompanied by photographs of mask wearing, overrun hospitals, and even the anti-mask brigade.

A forgotten time. The reason for the 1918 pandemic becoming suddenly visible is obvious, but the reason it was hidden earlier, I believe, echoes what is happening now: the people back then just wanted to move on. And so, after over two years of living with one form of lock-down or another, we crawled cautiously into the daylight and grabbed for whatever normal we could find. The normal we knew was never coming back, we understood that, so we settled for a shadow of normal in this new, more cautious world.

My wife and I can still go into town, visit the market stalls, and have a cup of tea at our favourite café, and we do our weekly shop like we used to do in the Before Time, but there are things we took for granted back then that are no longer available, which makes our lives just a little bit darker.

For one, I used to be able to get a doctor appointment. That is all but impossible now. And if I fell and broke my leg, I could be sure that an ambulance would come for me in short order. These days we are, literally, being told to get ourselves to A&E, and good luck getting anyone to have a look at you once you arrive. We have also grown used to not being able to get everything we want when we shop. Products, and services, come and go and, often, remain gone. Almost every shop, café, restaurant, pub, supermarket, or service is woefully short of staff, which often makes outings—to eat, shop, have a dislocated shoulder looked at, or plan an event—more fraught (and expensive) than before.

(This, by the by, isn’t only due to fallout from the pandemic, it is mainly down to that other thing that we are not supposed to mention—the “B” word—because bringing that up would be unpatriotic, a tactic that is uncomfortably similar to other, less savoury administrations.)

Ve are a peaceful country, so don’t mention ze Special Military Operation, or ve vill have you shot. This, however, is as normal as we are going to get for the foreseeable future, and it’s not all bad—there are some habits the pandemic instilled in us that linger on, and others that I wish did.

For example:

- It is still possible to cross the road to avoid someone you don’t want to talk to, and not seem rude. It is no longer necessary (indeed, it likely never was) but, this being Britain, it is likely to stick around for a while.

- Pocket-size hand-sanitizer: I carry one around with me all the time, and I plan to continue to do so. It’s a really convenient way to clean your hands, especially after using a public loo that has long ago been vandalized so none of the faucets work.

- Mask protocol: Masking up is still expected in some places, such as care homes or hospital wards, and I support this. In fact, I think it should have always been the case. Many people in those places would not respond well to a common cold, let alone Covid. And you naysayers can rail against it all you like, but the fact is, masks prevent the spread of disease. Why do you think surgeons wear them when they are operating?

- Contactless Transactions: I have to admit I was not a fan, but that was down to me being an old curmudgeon. Being able to pay for things without actually touching anyone or anything is quick, easy and germ-free. And these days, it doesn’t necessarily cut one off from human interaction, as I get to talk to the person operating the till while I am doing it. (I do, however, avoid using self-checkouts whenever possible, as I see that as the store taking a job away from someone and making me do it for free.)

- On-Line shopping: It was around before, of course, but it really took off during lockdown. Again, I try to buy local and face-to-face, if possible, but no shop anywhere has everything always available, and the Internet does.

Not available in Tesco. One thing that was immediately dropped that I wish was enforced was the one-way system. It was so nice, as we were being let out of lockdown, to be able to walk down a crowded street, or in a shopping mall, without having to navigate around people who refuse to get out of your way. It was maddening, and I so wished for a nice, orderly system. Then they had one, but as soon as they could, they reverted.

Seriously, we need to keep this. Mores the pity.

And so, we enter 2023 with trepidation, and facing a future a bit bleaker than the past, but whenever my mind starts dwelling on that, I remind myself of one final truth: at least no one is dropping bombs on us.

Zay are not bombs, zay are liberation packages.