-

End Game

I am in the final half of the final step in the final book of the Talisman series. I call this step The Robot Read—the last run through the manuscript after the writing, the revisions, the line editing and the proof-reading. And it always makes me shake my head in wonder and chagrin.

Writing is agonizing, editing is hard, and editing your own stuff is impossible. I would say it’s one of the major drawbacks of self-publishing, but even on those occasions when I placed books with actual publishers (who actually paid me, and not the other way around), the tasks of editing and proof-reading fell largely to me.

Editing. Someone’s got to do it, but let’s hope it’s not me. From what I hear, this is becoming the norm, so the advantage of an actual publisher is beginning to diminish.

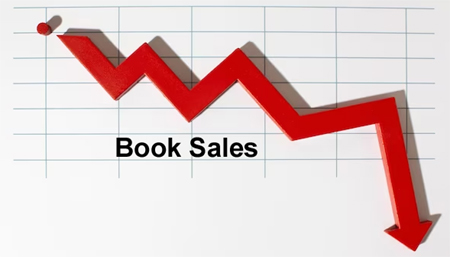

With those onerous tasks taken out of the hands of capable professionals and handed to us amateurs (just because you can write doesn’t mean you can edit) the best thing about a real publisher then became their marketing department, but this, too, is becoming more and more the responsibility of the author (which is really a shame because writers of all talent levels tend to be rubbish at marketing).

Basically, unless you’re an author pumping out bestsellers, the only advantage of a publisher is the kudos of having a publisher, as opposed to being the literary equivalent of an Incel who has to do the deed themselves.

What the Robot Read involves—after making the manuscript as free of errors as is humanly possible (and therefore being, by that time, so sick of the story that I want to scream)—is turning on Microsoft’s Read Aloud function, and listening to a monotone, robotic voice read my manuscript back to me. Following along, with the text magnified to 200%, is a great way to ferret out misused words, blatant errors, awkward syntax, and misplaced punctuation. And all that is there, in abundance.

Will Robinson: It…was…the…best…of…times…

it…was…the…worst…of.. times…While one would expect the manuscript to be nearly error-free by that time, the Robot Read unearths at least one or two, and often three, or four, or more, errors on each and every page. For a 280-page book (which this one happens to be) that’s approximately 900 additional errors that would have ended up in the final version had I not suffered through four days of listening to Hazel (other voices are available) parrot my words back to me.

Seriously, you have the choice of three different voices.

This is for the UK version; there are other voices

for the US version.And I have no illusions that this removes all the errors, but I can sleep easier knowing that I caught a couple hundred that I otherwise wouldn’t have, which allows me the satisfaction of assuming (perhaps optimistically) that I am releasing a book that is 97% error free. (97%, because nothing is 100% error-free, and 95% sounds too low.)

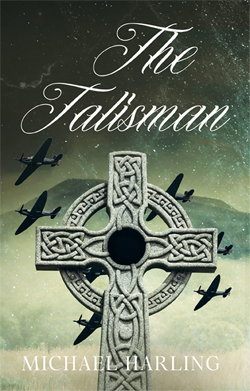

This final book—The Talisman—has been both easier and more difficult than I imagined. I was pleased to discover that the manuscript—finished in 2020—was in pretty good shape, meaning I could do the revisions in a relatively short time, as opposed to the year of grinding agony that Book VI gave me. Yet, at the same time, my anxiety level was strangely elevated.

The Talisman–certainly not coming to bookstore near you. I have lain awake in the early hours worrying that I have the details incorrect, and once woke up in a fright at four in the morning, realizing I’d had my female lead in a blue dress in chapter 36 and a brown skirt in chapter 24. I’m happy to report that the Robot Read put this issue to bed, and helped me sort out where to appropriately use hay versus straw.

I expect to finish the Robot Read over the next few days. After that, there is a bit of admin to attend to, and then the series will be released (re-released, actually) and the Big Publicity Push will commence, whatever that might be.

I’m hoping to come up with something, but I’m not terribly optimistic because, as you know, most writers are rubbish at marketing.

My marketing plan. Meanwhile, back in the editing department…

I am still looking for beta readers, especially for the more recent books. These are: The White Feather (about WWI), The Isle of Avalon (about the battle of Camlann), and The Talisman (about the Battle of Britain). If you would like a copy of any of those books, I will send you one if you are willing to read it and report any errors back to me. After making the corrections, I will send you an updated book.