Cruising

When you go on a cruise, the first thing that impresses you (or, at least, people like my wife) is the price. It’s not cheap. But, of course, people will say, “Everything’s included, so that makes it worthwhile.” And the second thing that impresses you is the price: true, your food is included (in certain venues), you can swim for free, and the view won’t put you out of pocket, but everything else—even staying in your room—has a price tag.

Drinks are not free, and the Tier System to buy a Drinks Package is so complicated we just pay as we go. And there is a daily charge—per person—for “Crew Appreciation” added to your credit card, which amounts to hundreds of dollars. For people who saved for years to come on such a trip, surprises like these can ruin your holiday.

Another cost is Internet access. We get the Intra-net for free, but if you want to access your email, you have to pay, and we decided it wasn’t worth it, which left me with the question of how long I could go without WiFi access before I gave in. The answer is: twelve hours.

The first night—getting on the ship, checking into our room, having dinner—it wasn’t a problem, but when I got up in the morning and brought my laptop to the (very nice and extremely handy) café on the Lido Deck, I found my programs were not happy with lack of access, so I had a look at what it cost and found that it wasn’t terribly expensive (compared to other things on this floating luxury hotel). All that remained was to convince my wife that it was worthwhile, and, to my surprise, she readily agreed. My wife might be frugal, but she does like her Wordle in the morning.

And so, we settled in.

I have written before that my wife and I don’t go on holiday so much as we simply live somewhere else for a while. Accordingly, as soon as we had a stable environment (the hotel might be moving, but at least we’re in the same room every night) we relaxed into a comfortable routine. As is my habit, I rise early, go to the café to write and wait for my wife to join me, whereupon we have breakfast. After that, we go for a bracing stroll around the decks, maybe stop for another cup of coffee (the tea here is shite) at the café, until it’s time for lunch, which we also eat in the café (it’s a really good café). After that, we sit by the Lido pool and read or watch the scenery, have a few drinks, and wait for dinner, which we take in the formal dining room, where we enjoy stimulating conversation with other guests that often goes on until it’s time for us to retire to our room to read and go to sleep at a reasonable hour, just like at home, while everyone else is out at one of the many venues, drinking and dancing and generally carousing, like you are supposed to do on holiday. I sometimes wonder if I should be concerned about that, or perhaps lobby for a change in our routine, but I just can’t muster the energy to care.

The third thing that impresses you when you go on a cruise (if you’re like my wife, bless her socialist little heart) occurs after about the third day, when you begin to notice hundreds, perhaps thousands, of young people constantly (though unobtrusively) sweeping and polishing and washing and buffing and serving and cooking, and you realize that there is an immense, unseen machine grinding away 24/7 to keep the 2,700 people on board fed, watered and happy. Who are they? Where do they all come from? (On our boat, Indonesia, mostly.) And what are they paid? Then you start to wonder if that exorbitant “Crew Appreciation Fee” is enough and start thinking about how you can give them more.

And then other questions arise: I take a shower every morning, along with about 2,700 other people. There are 2,700 toilets (plus those for the crew) flushing several times a day. Where does all that clean water come from? And where is all the sewage stored? (I at least have an answer for that: it isn’t stored, they flush it into the ocean. It’s true, I checked.)

I also found out that, when the ship docks, we get off at 9AM, and the next lot of 2,700 passengers begins to board at 11:30AM. Between those times, the crew turns the entire ship around: clean and prep all cabins, empty what needs emptying and fill what needs filling, get all the catering on board, top up their gas tank, or whatever they run the ship on—diesel, coal (although I haven’t see anyone with a shovel in their hand all week), nuclear fuel, or a fresh lot of hamsters for the big wheel. It’s a mammoth task, and the thought of it humbles us, makes us feel slightly guilty, and confirms that we are not the sort of people who should go on cruises.

Juno

It wasn’t all about cruising. On our trip, we stopped at three locations—Juno, Ketchikan and Skagway—where we had the option of doing nothing or choosing from a variety of excursions which catered to everyone’s income bracket. Naturally, we chose the $40-50 options, but there were excursions that cost $200, $300 or as much as $500. Each. Thankfully, they seem to recognize that not everyone who comes on a cruise has money to burn. Our $44.95 didn’t buy us a helicopter ride over the mountains, but it did get us a nice tour of the countryside and a hike to a lovely waterfall.

Juneau, our guide told us, was special in two ways: it is the capitol of Alaska, and it is cut off from civilization, meaning that anyone (or anything) coming in or going out must do so by boat or air. The capitol? Eh, someone had to do it. But being cut off, I found that fascinating, until I learned that many of the municipalities in the Alaskan Panhandle are similarly cut off. Having an actual road linking you with the rest of the state is more unusual.

It has a population of around 32,000, which is somewhat smaller than Horsham, and it looks a bit tired, but this may be due to having suffered (along with every other tourist destination on the planet) two lean years. Our guide told us that, over the past two years, they had hosted only 27 cruise ships. This year, so far: 400.

After being released from our tour, we wandered up the road, and down the road, and didn’t see much. There is an old church, and a famous saloon called The Red Dog, which I had never heard of, and not much else.

Ketchikan

Ketchikan was the final town (I won’t call it a city; there are only about 8,200 people there) we visited, but it was only our second favourite, so that’s why I’m putting it here.

Ketchikan wasn’t tired-looking (like Juneau); it was busy. It’s a working town, with people doing jobs that don’t all cater for the hundreds of cruise ships that dock there every year.

Oh, and Ketchikan is also cut off from the rest of the State.

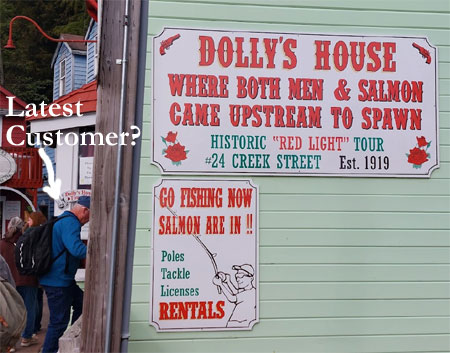

We did a tour of the rain forest and Totem Pole park, which was informative and worth the $49.50 price. In Ketchikan itself, we toured Creek Street, which is a favourite tourist destination, though not for the reasons it was 100 or so years ago.

Skagway

Skagway was far and away our favourite port. First of all, you just gotta love the name. And I liked it even better when I learned that it was a mispronunciation of the First Nations people’s (that’s what we’re calling them this decade; apparently Native Americans is so 1990) word for the area which roughly translates to “only a complete moron would live there!” Or something along those lines. The weather is now, and always has been, abysmal.

The town is tiny. Only about 1,200 people live there, but they keep the main street—which runs the length of the town—looking much as it did during the Gold Rush era, and of course they cater to the millions of tourists who swarm in from the big ships on a daily basis from April to October. It isn’t really a town so much as an open-air museum, with a few houses scattered along the side-street where their inhabitants hunker down for the apocalyptic winters.

We went on a tour up the mountain with a young woman named Melissa, who—at 8:30AM—was so perky I swear she must have got up at 5:00 to drink seven cups of espresso before driving her bus out to meet us. She was fun and funny, and she drove us up the mountain road telling stories and stopping at viewpoints along the way, until we reached the summit, where it was windy and cold and so clouded over that we couldn’t see a thing. But at least we got a photo next to the Welcome to Alaska sign.

We had to take our passports with us, even though we never crossed the border into Canada. This was because the border crossing—where the guards are—is about ten miles inside Alaska, down the mountain a bit. And the reason of that is because the weather at the real border is so harsh, they literally cannot operate there.

One of Skagway’s claims to fame is that it is connected to the outside world by rail and road. In your face, Ketchikan! It was also a town created for the gold rush, years before the gold rush happened.

Here’s the truncated version: William “Billy” Moore, believed that gold lay in the Klondike, based on the terrain, etc. So, in 1887, he and his son, Ben, claimed a 160-acre homestead at the mouth of the Skagway river, built a log cabin, a sawmill and a wharf, and waited for the prospectors to pass through. They weren’t there to dig for gold, they were going to get rich selling them supplies.

They waited ten years, but come they did. And hardly anyone found any gold to send back home. The biggest export from the Klondike were tall tales about the bounty awaiting anyone stupid…um, I mean, brave enough to come claim it.

This is what gave rise to The Red Dog Saloon, which was always a tourist attraction, and never an actual pub, and a lot of the businesses in Skagway, Ketchican, other Panhandle settlements, and even Seattle.

It’s a great story, and it may even be true. But true or not, I’m going back to somewhere warmer.

Next up: Vancouver, and the Year of the Glaciers

3 Comments

glenn

good post. if i didnt like the idea of cruise ahips before…… gm

John Doe

Waste water on cruise ships is treated internally just like a sewage plant onshore. Only treated sewage is discharged and it does not cause pollution. Much is recycled just like onshore.

MikeH

Thanks! That’s sort of reassuring.